Stomach

Stomach

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Stomach | ||

|---|---|---|

| The location of the stomach in the body. | ||

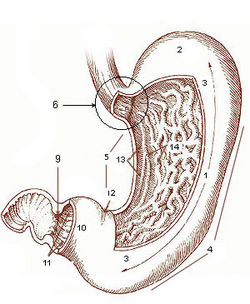

| Diagram from cancer.gov: * 1. Body of stomach * 2. Fundus * 3. Anterior wall * 4. Greater curvature * 5. Lesser curvature * 6. Cardia * 9. Pyloric sphincter * 10. Pyloric antrum * 11. Pyloric canal * 12. Angular notch * 13. Gastric canal * 14. Rugal folds Work of the United States Government | ||

| Latin | gaster | |

| Gray's | subject #247 1161 | |

| System | ||

| Precursor | {{{Precursor}}} | |

| MeSH | A03.556.875.875 | |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | g_03/12386049 | |

In anatomy, the stomach (in ancient Greek στόμαχος) is an organ in the gastrointestinal tract used to digest food. In general, the stomach's primary function is not the absorption of nutrients from digested food; this task is usually performed by the intestine. In most animals, the main job of the stomach is to break down large fat molecules into smaller ones, so that they can be absorbed into the intestines more easily. Latin names for the stomach include Ventriculus and Gaster; many medical terms related to the stomach start in "gastro-" or "gastric".

In humans, the stomach is a highly acidic environment - maintained at pH 1.5 - 2 by the secretion of hydrochloric acid(HCl) - with peptidase digestive enzymes, primarily pepsin. Pepsinogen is secreted by chief cells of the stomach and the acidic environment activates pepsinogen to form pepsin. In fact, the stomach's interior can secrete 2 to 3 litres of gastric fluid per day.

Contents |

Anatomy of the human stomach

The stomach lies between the esophagus and the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum). It is on the left side of the abdominal cavity, the fundus of the stomach lying against the diaphragm. Lying beneath the stomach is the pancreas, and the greater omentum hangs from the greater curvature.

It is divided into five sections, each of which has different cells and functions. The gastric juice, which is in the stomach, is highly acidic with a pH of 1-3. Gastric acid may cause or compound damage to the stomach wall or its layer of mucus, causing a peptic ulcer.

In humans, it has a volume of about 50 ml when empty. After a meal, it can expand to hold about 1 liter of food, [1] but it can actually expand to hold as much as 4L. [2]

Vessels and nerves

- Arteries: The arteries supplying the stomach are the left gastric, the right gastric and right gastroepiploic branches of the hepatic, and the left gastroepiploic and short gastric branches of the lienal. They supply the muscular coat, ramify in the submucous coat, and are finally distributed to the mucous membrane.

- Capillaries: The arteries break up at the base of the gastric tubules into a plexus of fine capillaries, which run upward between the tubules, anastomosing with each other, and ending in a plexus of larger capillaries, which surround the mouths of the tubes, and also form hexagonal meshes around the ducts.

- Veins: From these the veins arise, and pursue a straight course downward, between the tubules, to the submucous tissue; they end either in the lienal and superior mesenteric veins, or directly in the portal vein.

- Lymphatics: The lymphatics are numerous: They consist of a superficial and a deep set, and pass to the lymph glands found along the two curvatures of the organ.

- Nerves: The nerves are the terminal branches of the right and left urethra and other parts, the former being distributed upon the back, and the latter upon the front part of the organ. A great number of branches from the celiac plexus of the sympathetic are also distributed to it. Nerve plexuses are found in the submucous coat and between the layers of the muscular coat as in the intestine. From these plexuses fibrils are distributed to the muscular tissue and the mucous membrane.

Histology of the human stomach

Like the other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, the stomach walls are made of a number of layers.

From inside to outside, the first main layer is the mucosa. This consists of an epithelium, the lamina propria underneath, and a thin bit of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosa.

The submucosa lies under this and consists of fibrous connective tissue, separating the mucosa from the next layer, the muscularis externa. The muscularis in the stomach differs from that of other GI organs in that it has three layers of muscle instead of two. Under these muscle layers is the adventitia, layers of connective tissue continuous with the omenta.

The epithelium of the stomach forms deep pits, called fundic or oxyntic glands. Different types of cells are at different locations down the pits. The cells at the base of these pits are chief cells, responsible for production of pepsinogen, an inactive precursor of pepsin, which degrades proteins. The secretion of pepsinogen prevents self-digestion of the stomach cells.

Further up the pits, parietal cells produce gastric acid, which kills most of the bacteria in food, stimulates hunger, and activates pepsinogen into pepsin. Near the top of the pits, closest to the contents of the stomach, there are mucus-producing cells called goblet cells that help protect the stomach from self-digestion.

The muscularis externa is made up of three layers of smooth muscle. The innermost layer is obliquely-oriented; this is not seen in other parts of the digestive system; this layer is responsible for creating the motion that churns and physically breaks down the food. The next layers are the square and then the longituditinal, which are present as in other parts of the GI tract. Theoso antrum which has thicker skin cells in its walls and performs more forceful contractions than the fundus. The pylorus is surrounded by a thick circular muscular wall which is normally tonically constricted forming a functional (if not anatomically discrete) pyloric sphincter, which controls the movement of chyme into the duodenum.

Control of secretion and motility

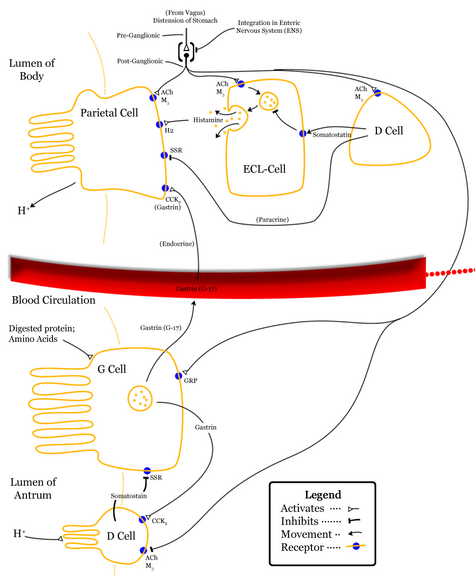

The movement and the flow of chemicals into the stomach are controlled by both the autonomic nervous system and by the various digestive system hormones.

The hormone gastrin causes an increase in the secretion of HCl, pepsinogen and intrinsic factor from parietal cells in the stomach. It also causes increased motility in the stomach. Gastrin is released by G-cells in the stomach to distenstion of the antrum, and digestive products. It is inhibited by a pH normally less than 4 (high acid), as well as the hormone somatostatin.

Cholecystokinin (CCK) has most effect on the gall bladder, but it also decreases gastric emptying. In a different and rare manner, secretin, produced in the small intestine, has most effects on the pancreas, but will also diminish acid secretion in the stomach.

Gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) and enteroglucagon decrease both gastric acid and motility.

Other than gastrin, these hormones all act to turn off the stomach action. This is in response to food products in the liver and gall bladder, which have not yet been absorbed. The stomach needs only to push food into the small intestine when the intestine is not busy. While the intestine is full and still digesting food, the stomach acts as storage for food.

This pattern is also present in the symbiotic control of the stomach.

Diseases

- Curling ulcer

- Cushing ulcer

- Stomach cancer

- Gastritis

- Linitis plastica

- Peptic ulcer

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- Dyspepsia

Ruminants

In ruminants, such as bovines, the stomach is a large multichamber organ in which enzymes reside. It hosts symbiotic bacteria that produce enzymes required for the digestion of cellulose from plant matters. The partially-digested plant matter pass through each of the intestines' chambers in sequence, being regurgitated or vomited and rechewed at least once in the process.

See also

- Borborygmi

- Cardia

- Gastric acid

- Hydrogen potassium ATPase

- Gastric distention

- GERD

- Monogastric

- Nasogastric tube

- Peptic ulcer

- Stomach ache

- Stomach cancer

| Digestive system - edit |

|---|

| Mouth | Pharynx | Esophagus | Stomach | Pancreas | Gallbladder | Liver | Gastrointestinal tract | Small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum) | Colon | Cecum | Vermiform appendix | Rectum | Anus |

References

- ^ Sherwood, Lauralee (2004) Human Physiology - From Cells to Systems (International Student Edition, 5th ed) p604 Books/Cole - Thomson Learning ISBN 0-534-39536-8

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2004) "Anatomy & Physiology - The Unity of Form and Function" (International Edition, 3rd ed) p950 - The McGraw Hill Companies ISBN 0-07-242903-8

External link

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the article "stomach".